My portal into poetry came in large part through the pop and rock songs I listened to as a teenager and 20-something. I know this is true for a lot of poets.

One musician from my youth whose music and lyrics had a particularly deep and resonant effect on my spirit was Joni Mitchell. The first record of hers I discovered and wrapped myself around completely was Blue. I was 16 or so and in the midst of having my heart broken for the first time. That record was like a mother’s arms in which I was cradled for a few weeks while the bleeding stopped. Ironically or not, it was the heartbreaker herself who gave me the record. (Was it for want of torture that I listened to it—or comfort?) Regardless, it was Christmastime and I’d gone to my aunt and uncle’s in a tiny town in Central Illinois to celebrate with my family. It was cold and snowy outside on Christmas Eve and I remember singing hymns while holding a candle in the Methodist church that inside was warm, dark and snug—as if it had been carved from the inside of an enormous tree.

I will never forget how despondent I was, sulking those few days while listening to “River” and “Little Green” over and over on my Walkman.

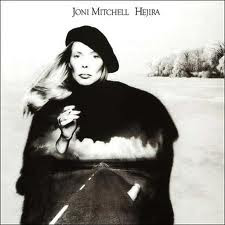

As the years went on I bought everything by Joni and she became a kind of muse to me. Her lyrics are musical, wise, tough, cynical, critical, empathic, symbolic, iconoclastic, imagistic, archetypal, sensitive and deeply personal—everything I believe poetry should be. The albums that left the deepest impressions on me are Blue, Hejira, The Hissing of Summer Lawns and her live album, recorded with the L.A. Express, Miles of Aisles.

Hejira is such an interesting record. It’s haunting in its mood. Solitary. Detached. Meditative. I believe what happens with certain artists and musicians whose work speaks loudest to us is it wakes something up in us, an awareness and familiarity that are innate, latent or dormant inside. Some of this is universal, some unique to a select collective of people. And I think a lot of what gets awakened is the archetypal structures for poetry and song and rhythm and feeling that are built into our DNA.

We all have certain artists who speak to us at various times in our lives. But only a few actually make it to the point of being teachers, guides or gurus; we actually become a bit like them, or a part of them becomes a part of us. I’d say this is true for Joni. Thirty years later, bits and pieces of her lyrics will pop into my mind as snippets of poetry, something alliterative, a metaphor, a phrase turned just right and relevant to the moment.

Today, listening to my iPod on shuffle, her song “Jungle Line” from The Hissing of Summer Lawns came on. It’s not one of her signature melody pieces, but lyrically a stream-of-consciouness homage to jazz and its origins. And like so many of Joni’s songs, it tells a story. This may be what I am attracted to most in Joni’s music—the paradox of often comforting melody alongside dark, cynical lyrics critical of the absurd, middle-class American lust for status and stuff. This is particularly true in her later albums, which get darker both lyrically and melodically the further in the chronology.